“My grandmother’s hands feel leathery. They are never soft or smooth. No amount of lotion can unharden the skin after years spent cleaning, scrubbing, cooking. Hands immersed in dirty water, clean water, harsh chemicals—hands that, combined with elbow grease, shined floors and windows and baseboards in white women’s kitchens. Hands of an older, Southern Black woman . . . hands that quietly built a nation but whose history is often unrecorded. I have no memory of manicured hands holding mine. Instead, when I remember her hands, I can still feel the calluses of someone who only knew labor her whole life.

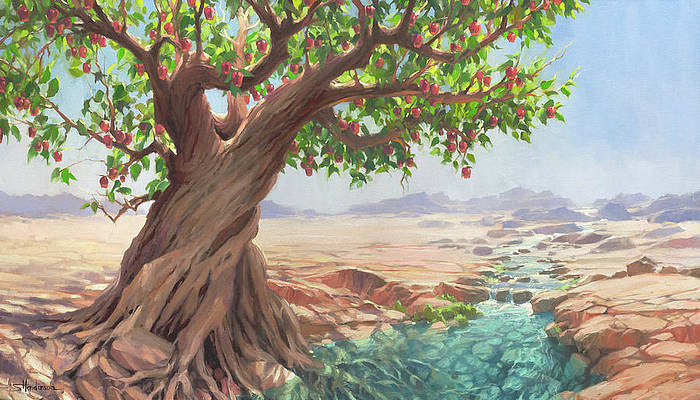

It is only now that I am much older that I can piece together the work of her hands. Strong young hands cutting tobacco in Southern fields; brown hands cradling the one long-desired child she dared to love after so many losses; tentative hands signing legal documents she did not understand for a new life up North; gentle hands walking her abandoned granddaughter to school. My grandmother’s hands are a love story, but they are not smooth, not soft, not easy. No real love story is. Her hands are a love story of survival in hard places, during hard times.

These hands parted small sections of hair, oiled a dry scalp, and made neat piles of shiny braids. These same hands, which had scrubbed toilets and diapered other women’s babies, would take the smallest of barrettes or beads or balls and place them securely at the end of tiny plaits, in alternating patterns and colors, securing them at the ends with tiny rubber bands. The creativity of brown hands, denied an artist’s palette, found joy in arranging the colorful beads of her granddaughter’s hair. These hands, which had never touched a potter’s wheel or blank canvas, created beauty from braids. Rough, callused, heavy hands loved my tender young scalp. These hands, so large to my child’s eyes, threaded an impossibly tiny needle, and from fabric scraps they made dolls and quilts and magic. I would later have no trouble believing in the creatio ex nihilo—the idea that God created the cosmos out of nothing—because all my life I had watched my grandmother prepare a feast from an empty refrigerator and bare cabinets. She taught me that to be a Black woman in this world is to learn how to make something from nothing.

Sometimes I look at my professionally manicured hands and feel a sting of hot shame. Shame at not being able to fully comprehend the generational sacrifices made on my behalf. Shame for ever having been embarrassed to wear Easter dresses sewn by those hands when my friends wore fancier ones purchased at Macy’s. Shame for once rejecting the food those hands cooked in favor of something at the local fast-food place. And shame when I wonder whether my hands will ever produce something that leaves so enduring a legacy.”

— Yolanda Pierce

“In My Grandmother’s House: Black Women, Faith, and the Stories We Inherit”

click here to download this week's bulletin!